All around the United States, school districts are banning books as a result of pressure from parents and advocacy groups with the claim to protect the youth; however, EHPS believes in open communication and opportunities to learn.

A book ban is not a literal ban; it is the canceling, or the censorship of books. Book bans usually occur because of peer pressure, a misunderstanding, or offensive language. Executive Director at the Connecticut Democracy Center, Sally Whipple, says that a potential reason why people ban books is because of offensive ideas or to protect children: “ I think some banning is motivated by a desire to protect children from ideas that some people feel will be upsetting or otherwise harmful. Other books may be banned because they use words or express ideas that some people find offensive or challenging to the status quo.” Though these are the usual motives for banning books, there can be other reasons as well.

EHHS English teacher, Mrs. Ashley Bogart believes that there are hidden motives for banning books: “ I think that a lot of the motivating factors behind book bans are kind of a guise in this idea of protection, like protecting children from things, but I don’t think that’s necessarily the actual motive. I think people have their own agendas.” Some topics that are commonly looked down upon by those who ban books are gender identity, sexual references, death, and violence. Especially when it comes to children, exposure to topics such as these tends to be restricted.

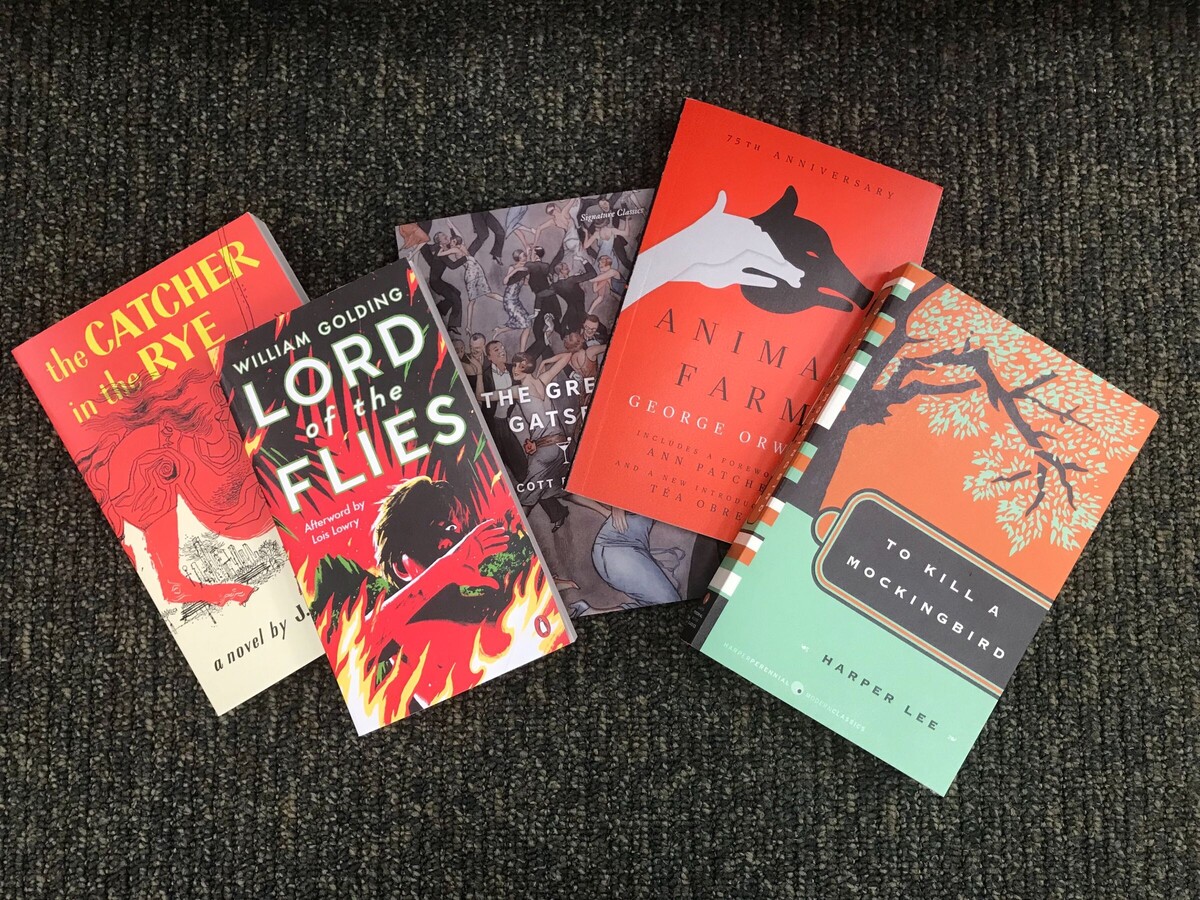

In the United States, book bans commonly take place in schools. Some books that are commonly banned in schools include Animal Farm, To Kill a Mockingbird, Lord of the Flies, The Catcher in the Rye, and many more. Though many school districts have banned certain books, EHPS has not banned any books. According to EHHS English teacher, Ms. Haley Lutar, EH school officials put trust in the teachers to make the right decisions when choosing what books to teach: “ The district kind of lets the professionals [administrators and teachers] make the judgment calls.” Ms. Lutar continues to mention how the books that are chosen to be taught in EH have a purpose, and aren’t chosen randomly: “[. . .] it’s not just done arbitrarily. If there’s not a reason for it, we typically don’t teach it.” The only time when schools in EH restrict access to a book is when it comes to age appropriateness.

According to EHHS Library Media Specialist Mrs. Patricia Robinson, there is a grade-level book ban policy. EHPS restricts books based on the age level given by each book publisher: “There is like a grade-level banned policy. If the publisher determines that the book is for say 13 through 18, then for me, I can put it out in the [EHHS] library. If it’s over 18 I prefer not to put it out because 99% of kids here [at EHHS] aren’t over 18.” EHHS English Instructional Leader Mrs. Lisa Veleas, says that challenging books can be beneficial if it creates discussion, but “not if it gets to the place where it’s saying you absolutely may not include that book in your library.” She continues, “I just don’t believe that’s okay, except in the cases of very explicit, inappropriate material for a school.”

EHPS Assistant Superintendent and curriculum writer Dr. Jennifer Murrihy agrees with the idea of open communication when challenging a certain book. She feels that having open communication between teachers, parents, and students is great for understanding others’ perspectives: “When we have good dialogue with our community, or with our teachers, or with our students about books we get a better understanding of people’s lived experience, so I think in a democratic society, whether you call it pushback or critical engagement, it can be a good thing.” Ms. Lutar shares this belief as well, also noting how this discussion can help teachers: “ I don’t think it’s bad to have a conversation about why [a book is taught] because reflection and improving is part of the world of teachers.” This allows teachers to grow and further improve their curriculum.

However, Mrs. Bogart notes that a con of challenging or banning books is that it creates stereotypes and learning gaps: “[Book bans] have the potential to create learning gaps, you could reinforce stereotypes, and not teach young people to develop their own opinions on controversial subjects.” Mrs. Veleas has a similar belief, saying that book bans send a negative message out to those who can personally relate to the content of a banned book: “I think in some cases it’s more of a message that the world is sending to people about what we think is okay to be as a person when we ban books, and that’s dangerous.” When discussing the impact of book bans on education, EHHS English teacher Mrs. Lisa Gardner says, “You’re not giving students a good view of what the world is like and what different kinds of people are like, which is ultimately going to impact their ability to empathize with other people, and become not knowledgeable about the world and the people around them.” Roxanne Coady, the founder of RJ Julia Booksellers in Madison, CT, agrees with this belief, saying that “[book bans] are detrimental to our developing an understanding of those that might be different from us and a hindrance to our being empathetic about the challenges that people with different backgrounds and experiences contend with.” Ms. Whipple also agrees, while also noting that book bans get in the way of people’s ability to problem solve and think clearly: “When we lose access to knowledge, points of view, and stories that force us to confront challenging information, our ability to think clearly, problem solve, and understand ourselves and others is diminished.” Referring to EH students, Mrs. Robinson believes that book bans don’t have much of an impact on students’ understanding of the world because, at EHHS, there are many kinds of books available in the Library Media Center (LMC): “We have so many multicultural and multi-interest, multi-version books that kids can pick from that they can learn really whatever they want through age-appropriate stuff that I have [in the LMC].” Ms. Coady believes that schools that ban books are forgetting their mission to educate: “I think that schools are forgetting and misinterpreting the definition of educating, namely, to inform our students on the breadth of our history, the mistakes of the past, and a way to create a future. Banning books is the opposite of educating.”

Based on what most have said, not many teachers and staff in EH are aware of book bans occurring in Connecticut. However, Dr. Murrihy recalled seeing an article about a controversial book at a Colchester public library, where several parents brought up concerns over a book that was about the drag queen, Ru Paul. A similar incident happened in Ms. Whipple’s hometown, where “a book banning woke people up to the dangers of censorship.” Ms. Whipple says that a positive outcome of this was that “[people in my town] formed a group to educate people about the impacts of book banning and to keep an eye out for new attempts at censorship.”

In EHPS, parents and students may ask permission for the student to read a different book in their English class. Mrs. Veleas says that it wouldn’t be right to force a student to read a book that causes them discomfort: “We have had students in the past that have expressed something that concerns them in terms of content and they’ve asked to read an alternative book maybe to something that’s in the curriculum. We always try and honor that. If there’s a legitimate concern about something and it’s going to cause a student distress, then that’s not what we’re looking for.”

There are no specific criteria to ban a book; it’s based on people’s beliefs and values. Some may be wondering if there are consequences of going against a book ban. The answer is no. A book ban isn’t a literal ban, so therefore there are no legal consequences for reading a banned book. Despite the problems book bans may cause, challenging books encourages open communication between schools and their communities, creating a stronger bond between the two.